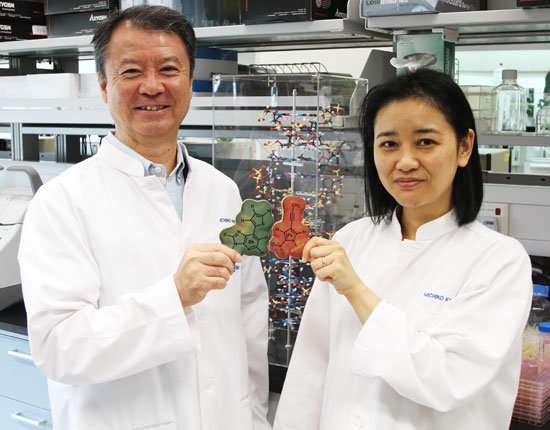

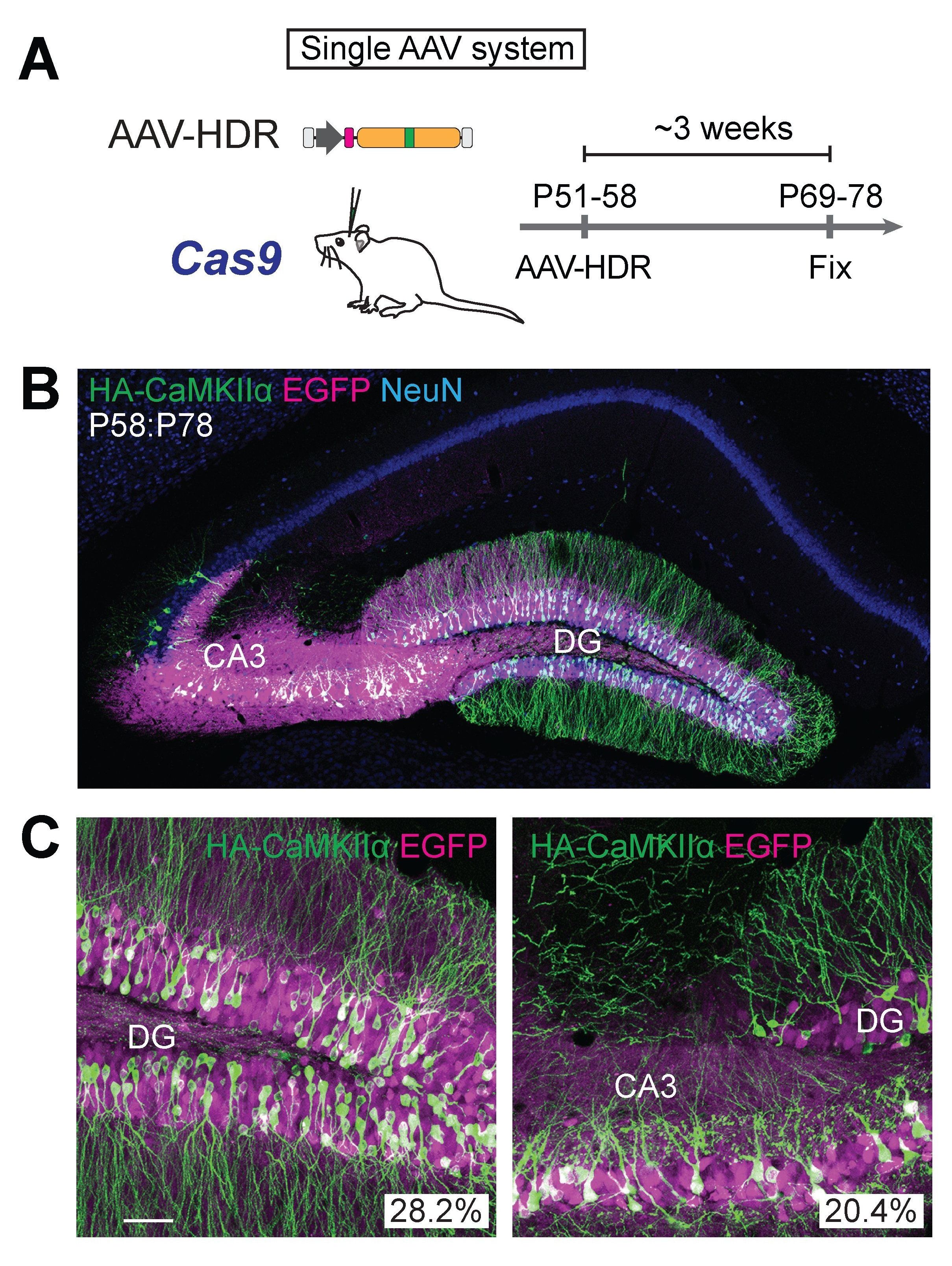

Genome editing technologies have revolutionized biomedical science, providing a fast and easy way to modify genes. However, the technique allowing scientists to carryout the most precise edits, doesn’t work in cells that are no longer dividing — which includes most neurons in the brain. This technology had limited use in brain research, until now. Research Fellow Jun Nishiyama, M.D., Ph.D., Research Scientist, Takayasu Mikuni, M.D., Ph.D., and Scientific Director, Ryohei Yasuda, Ph.D. at the Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience (MPFI) have developed a new tool that, for the first time, allows precise genome editing in mature neurons, opening up vast new possibilities in neuroscience research.

This novel and powerful tool utilizes the newly discovered gene editing technology of CRISPR-Cas9, a viral defense mechanism originally found in bacteria. When placed inside a cell such as a neuron, the CRISPR-Cas9 system acts to damage DNA in a specifically targeted place. The cell then subsequently repairs this damage using predominantly two opposing methods; one being non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), which tends to be error prone, and homology directed repair (HDR), which is very precise and capable of undergoing specified gene insertions. HDR is the more desired method, allowing researchers flexibility to add, modify, or delete genes depending on the intended purpose.

Coaxing cells in the brain to preferentially make use of the HDR DNA repair mechanism has been rather challenging. HDR was originally thought to only be available as a repair route for actively proliferating cells in the body. When precursor brain cells mature into neurons, they are referred to as post-mitotic or nondividing cells, making the mature brain largely inaccessible to HDR — or so researchers previously thought. The team has now shown that it is possible for post-mitotic neurons of the brain to actively undergo HDR, terming the strategy “vSLENDR (viral mediated single-cell labeling of endogenous proteins by CRISPR-Cas9-mediated homology-directed repair).” The critical key to the success of this process is the combined use of CRISPR-Cas9 and a virus.

Read more