When the gene-editing technology CRISPR first made a splash back in 2012, it foretold a future in which curing diseases might simply involve snipping out problematic bits of genetic code. Of course, innovation is rarely so straightforward. As incredible as CRISPR is, it also has some pretty sizable flaws to overcome before it can live up to its hype as a veritable cure-all for human disease.

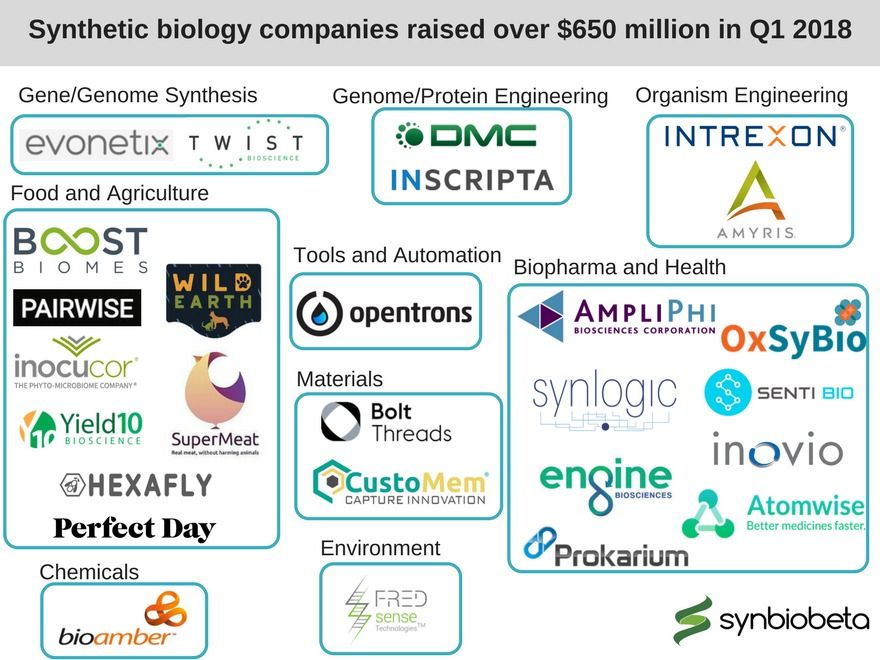

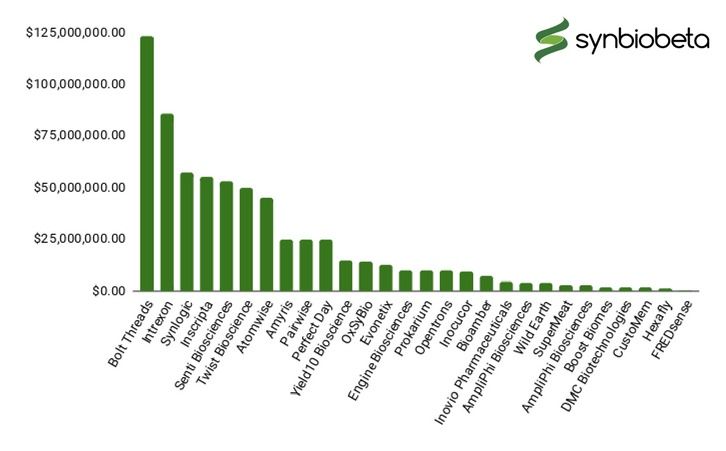

A new study published this week in the journal Nature Genetics tackles one CRISPR complication. CRISPR gene-editing systems can easily cut many pieces of DNA at once, but actually editing all those genes is a lot more time-consuming. Now, scientists at UCLA have come up with a way to edit multiple genes at once.

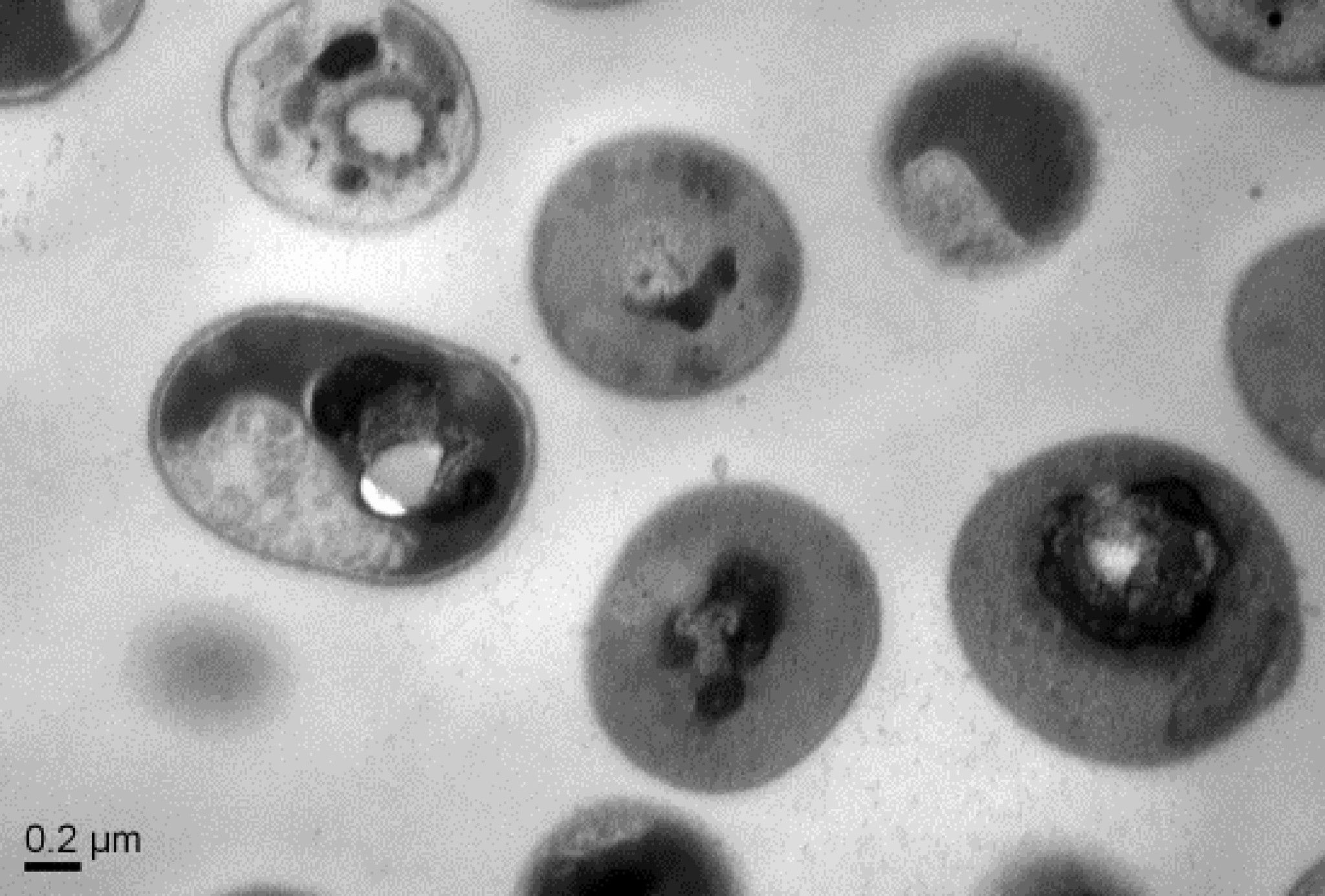

When scientists use CRISPR for genetic engineering, they are really using a system made up of several parts. CRISPR is a tool taken from bacterial immune systems. When a virus invades, the bacterial immune system sends an enzyme like Cas9 to the virus and chops it up. The bacteria then adds short bits of virus DNA to its own code, so it can recognize that virus quickly in the future. If the virus shows up again, a guide RNA will lead the Cas9 enzyme to the matching place in the virus code, where it again chops it up. In CRISPR, when that cutting is done, scientists can also insert a new bit of code or delete code, to, for example, fix disease-causing genetic mutations in the code before patching it up. But delivering that new code and making the patch is where it can get especially tricky.