A team of researchers from Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology has found that they could use an optical tweezer array of laser-cooled molecules to observe ground state collisions between individual molecules. In their paper published in the journal Science, the group describes their work with cooled calcium monofluoride molecules trapped by optical tweezers, and what they learned from their experiments. Svetlana Kotochigova, with Temple University, has published a Perspective piece in the same journal issue outlining the work—she also gives an overview of the work being done with arrays of optical tweezers to better understand molecules in general.

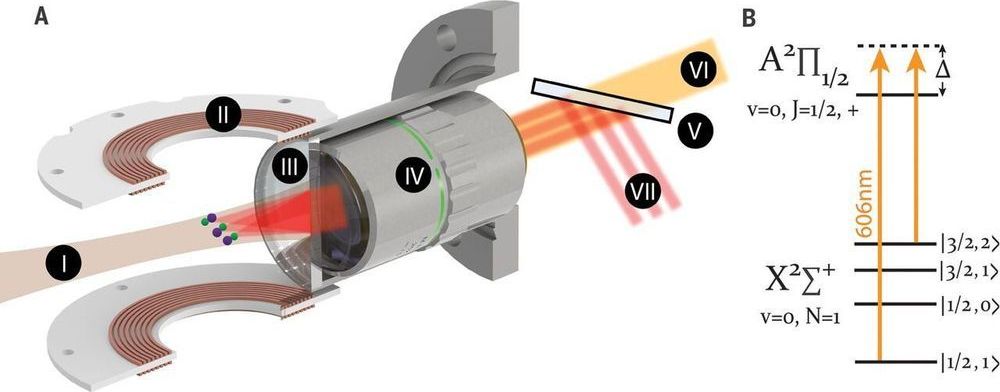

As Kotochigova notes, the development of optical tweezers in the 1970s has led to groundbreaking science because it allows for studying atoms and molecules at an unprecedented level of detail. Their work involves using laser light to create a force that can hold extremely tiny objects in place as they are being studied. In more recent times, optical tweezers have grown in sophistication—they can now be used to manipulate arrays of molecules, which allows researchers to see what happens when they interact under very controlled conditions. As the researchers note, such arrays are typically chilled to keep their activity at a minimum as the molecules are being studied. In this new effort, the researchers chose to study arrays of cooled calcium monofluoride molecules because they have what the team describes as nearly diagonal Franck-Condon factors, which means they can be electronically excited by firing a laser at them, and then revert to an initial state after emission.

In their work, the researchers created arrays of tweezers by diffracting a single beam into many smaller beams, each of which could be rearranged to suit their purposes in real time. In the initial state, an unknown number of molecules were trapped in the array. The team then used light to force collisions between the molecules, pushing some of them out of the array until they had the desired number in each tweezer. They report that in instances where there were just two molecules present, they were able to observe natural ultracold collisions—allowing a clear view of the action.