;-;

Salmonella bacteria flip an electric switch as they hitch a ride inside immune cells, causing the cells to migrate out of the gut toward other parts of the body, according to a new study publishing on April 9 in the open-access journal PLOS Biology by Yaohui Sun and Alex Mogilner of New York University and colleagues. The discovery reveals a new mechanism underlying the toxicity of this common food-borne pathogen.

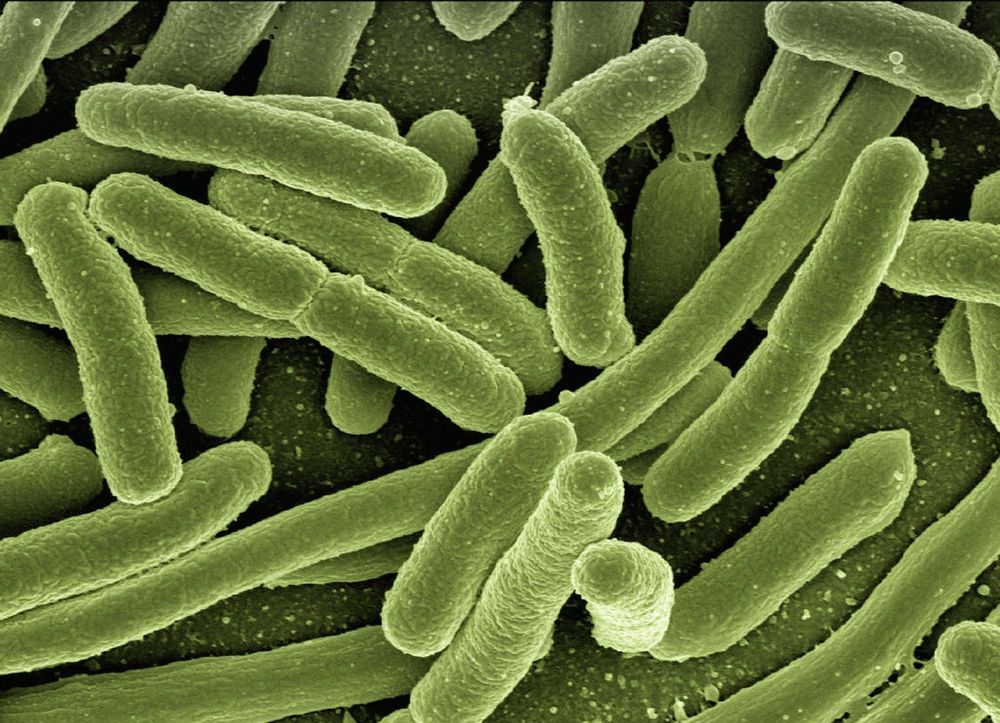

Salmonella are among the commonest, and deadliest, causes of food poisoning, causing over 400,000 deaths every year. Many of those deaths result when the bacteria escape the gut inside immune cells called macrophages. Macrophages are drawn to bacteria in the gut by a variety of signals, most prominently chemicals released from the site of infection. Once there, they engulf the bacteria as a regular part of their infection-fighting job. However, rather than remaining there, bacteria-laden macrophages often leave the site and enter the bloodstream, disseminating the bacteria and greatly increasing the gravity of the infection.

Tissues such as the gut often generate small electrical fields across their outer surfaces, and these electrical fields have been known to drive migration of cells, including macrophages. In the new study, the authors first showed that the lining of the mouse cecum (the equivalent of the human appendix) maintains a cross-membrane electrical field, and that Salmonella infection altered this field and contributed to the attraction of macrophages. Measurements of the polarity of the local charge indicated that the macrophages were attracted to the anode, or positively charged pole within the field. Once they engulfed bacteria, however, they became attracted to the cathode and reversed their migratory direction, moving away from the gut lining, toward vessels of the circulatory system. This switch was driven by a in the composition of certain charged surface proteins on the macrophages; the mechanism by which bacterial engulfment triggers this change is still under investigation.