Rosalinda Roberts had gotten used to seeing weird shapes in the brain. Over three decades of looking at brain tissue under an electron microscope, she’d regularly come across “unknown objects”—specks and blobs in her images that weren’t supposed to be there, and didn’t seem to relate to the synapses and structure that she was studying. “I’d just say, ‘well I’m not going to pay attention to that’” she explains. That’s all changed now.

Finding bacteria in the brain is usually very bad news. The brain is protected from the bacterial menagerie of the body by the blood-brain barrier, and is considered a sterile organ. When its borders are breached, things like encephalitis and meningitis can result. Which made it all the more surprising when Roberts, along with Charlene Farmer and Courtney Walker, realized that the unknown objects in their slides were bacteria.

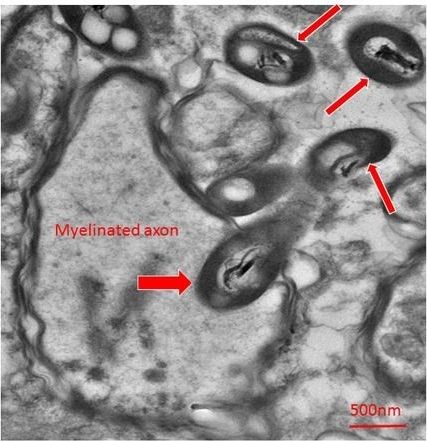

Many of them were caught mid-stride, entering neurons or penetrating axons. Others were in the process of dividing. They were picky, too, strongly preferring some regions of the brain over others. The surrounding brain tissue showed no signs of inflammation. If the bacteria were in the brain while the individual was alive, they were not pathogenic.