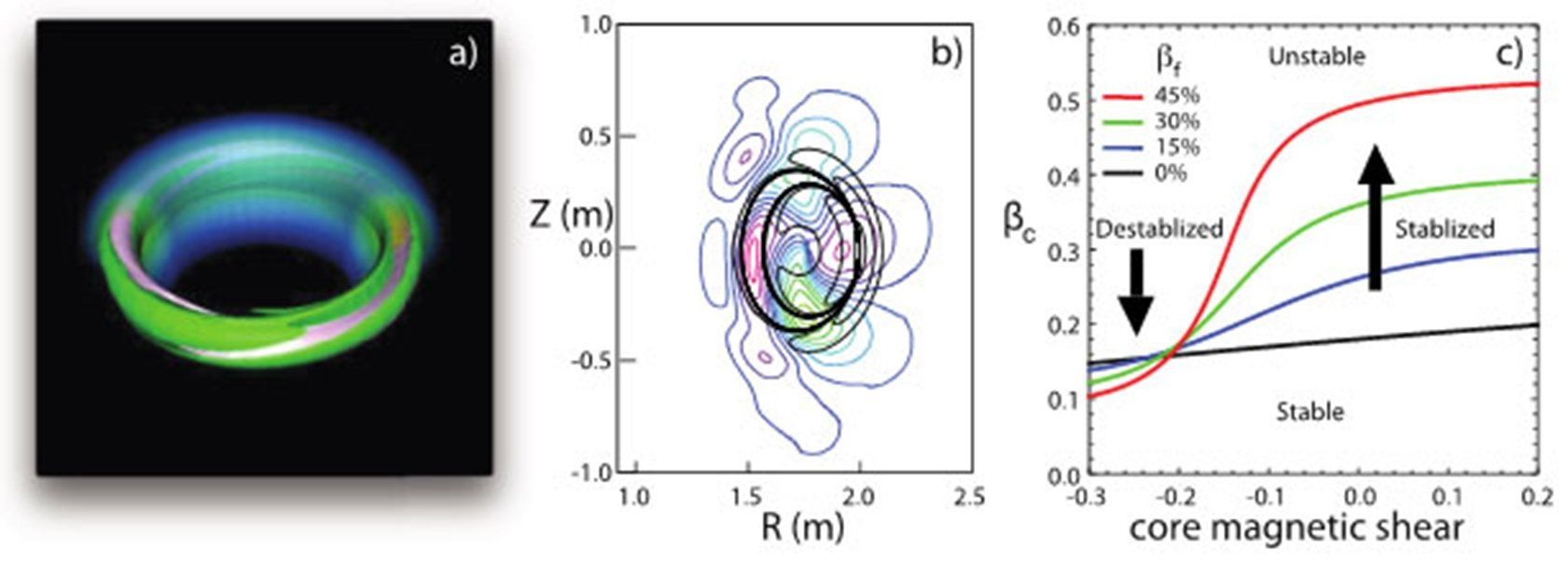

One of the greatest obstacles to producing energy via fusion on Eearth is the formation and growth of small magnetic field imperfections in the core of experimental fusion reactors. These reactors, called tokamaks, confine hot ionized gas, or plasma. If the imperfections persist, they let the energy stored in the confined plasma leak out; if allowed to grow, they can lead to sudden termination of the plasma discharge. Recent simulations of tokamak discharges with fast, energetic ions have shown that the structure of the magnetic field can either stabilize or destabilize these magnetic imperfections, or “tearing” instabilities. The result depends on the helical structure of the field as it winds around the tokamak.

Energetic ions, ubiquitous in fusion plasmas, can be a strong stabilizing or destabilizing force. The choice depends on the magnetic shear in the plasma. Understanding the physics driving the onset of the instabilities can lead to their avoidance, a “zero tolerance” approach, vital for ITER’s stable operation. ITER is a key step between today’s fusion research and tomorrow’s fusion power plants. Also, the results explain many experimental observations of tearing instabilities that limit the maximum heat energy that can be contained.

Advanced tokamaks achieve high-thermal-energy plasmas by injecting beams of hot ions that collide with, and thereby heat, the background plasma. Burning plasma experiments that create energy from fusion reactions, such as ITER, will also have a significant population of hot alpha particles, the byproduct of fusion. The effects that energetic ions have on the benign instabilities, such as the sawtooth instability, which causes the temperature near the plasma core to flatten, and the toroidal Alfvén eigenmode, which intuitively is a “vibration” (wobble) of the magnetic field lines, have been known for some time.