One of the things I love most about being a Surgical Oncologist is that I see my patients for years after I have treated them. However, my clinic days are inevitably like the opening scenes from the old Wide World of Sports television program that aired on Saturday afternoons on ABC. I remember watching this show on weekends as a child and teenager. The “thrill of victory”, with images of athletes crossing the finish line in first place, equates to those patients who receive good news during their clinic visit. I tell them I am confident I can perform an operation to remove their cancer; or I confirm that their blood tests and scans show that tumors have not recurred after surgery, chemotherapy, and other treatments; or we pass some major chronologic milestone without evidence of cancer rearing its ugly head again (many patients still believe the 5 year anniversary of being cancer-free equates with being “cured”, if only that were always true). In contrast, the “agony of defeat”, forever seared in my memory in the opening scenes of Wide World of Sports with the ski jumper falling off the end of the jump and bouncing hard off the slope, represents the distress and depression felt by patients and their family members when I deliver bad news.

I would never make it as a professional poker player because I can’t bluff when I’m holding a bad hand or keep from grinning when I have a good one. My patients can tell from my face when I walk into the clinic room what the news is going to be. When all of the blood tests and scans reveal no evidence of cancer recurrence, I walk in smiling and immediately tell all gathered in the room that everything looks great and I see no evidence of any cancer. The remainder of the visit becomes a combination of medical checkup and social enterprise. I inquire about the well-being of their children, grandchildren, parents, other friends and relatives I have met, their pets, their gardening, their recent travels, and sundry snippets of their ongoing lives. Patients frequently bring pictures of children and grandchildren, or travel photos of places they have been since their last visit with me. Often I’m asked for medical advice on conditions totally unrelated to their cancers as they get farther and farther away from that diagnosis. My patients also know about tidbits from my life. They ask about the status of soccer teams that I coached, how my son or daughter were doing in college (both graduated and onto successful careers, thank you), and whether I have progressed from owning a Ferrari lanyard to hold and display my medical badge (I’m a fan of Ferrari F1 racing) to actually owning a Ferrari automobile (I do not).

I am told by patients, family members, and members of my patient care team that I am quite solemn when I walk in a clinic room to deliver bad news. No “light-hearted” chatter or discussion of recent family events or outings occurs. The nervous, hopeful smiles on the faces of the patient and the family members in the room quickly fade as I describe what I am seeing on their blood tests and the scans I have reviewed. Friedrich Nietzsche, the pejorative poster boy of pessimism, is credited with the aphorism, “Hope is the worst of evils, for it prolongs the torments of man.” Thankfully, he was not involved in the care of patients with cancer or other chronic illnesses. A particular patient comes to mind when I remember the importance of dealing with both the highs and the lows of talking with cancer patients.

The patient in question was the wife of an Emeritus Professor of Engineering at a prestigious American university. The Professor knew a thing or two about scientific investigation, statistics, and assessments of probability. Mrs. Professor had a large, grapefruit-sized malignant vascular tumor in the center of her liver called an epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Quite a mouthful of a name for a rare malignant tumor of the liver. Her tumor was in an unfortunate location in the center of the liver and was wrapped around two of the three veins that drain all of the blood out of the liver into a large blood vessel called the inferior vena cava. The tumor was abutting a portion of the third vein. As a hepatobiliary surgical oncologist, I know I must preserve at least one of these veins to allow blood that flows into the liver to flow back out properly. She had seen surgeons at several other hospitals in the United States and was told that the tumor was inoperable and untreatable. If she was lucky, she might live a year, these doctors told my patient and her husband. The Professor contacted me, and I examined Mrs. Professor and evaluated her prior scans, and then obtained some additional high resolution scans to better understand the appearance of her tumor. I realized that her particular tumor had a very thick fibrous capsule surrounding it. I explained to the patient and her husband that it may be possible to remove the tumor, but that it would be challenging. This lady who had been sullen, withdrawn, and tearful every time I had met with them previously suddenly looked up and said, “If there’s any chance, I’m willing to take it!” I preceded the next week to perform an operation that removed the entire left lobe and a portion of the right lobe of her liver and I was able to gently dissect the tumor capsule free from the third hepatic vein. The operation was successful and the patient recovered well over the next several weeks.

The Professor, having lots of time on his hands, sent an acerbic letter to the physicians at the other hospitals, explaining in detail to them his mathematical analysis of the fallacy of their prognosis when considering an individual patient in terms of a statistical mean. He pointedly informed them that it was impossible to predict if any given individual would fall near the mean or several standard errors away from the mean. In plain language, the Professor was indicating that predicting the length of survival of cancer patients is usually based from data on the life-span of a large number of people diagnosed with the same disease. Some people live for a shorter, possibly even much shorter time than the average, while some live for significantly longer periods than the average survival time. Unfortunately, for the next year when I would encounter these various surgeons at national or international surgery or cancer meetings, I would get some frosty glares and very little conversation.

For the next three years, I saw Mrs. Professor every four months and with each visit I would enter the room smiling and pleased to report that all looked well on the blood tests and the scans. Unfortunately, three and a half years after her operation, the nature of the clinic visit changed. The moment I walked in the door of the room the professor said, “Uh oh!” Mrs. Professor immediately looked crest fallen and asked, “What is wrong?”. I sat down and explained to them that there were new small tumors in her liver and in her lungs. She asked how this could be possible since she felt so well, and I countered that small tumors frequently do not cause symptoms or problems that make the patient aware of their presence. I spent almost an hour answering an array of questions from my patient and the Professor, many of which were different ways of asking me to predict the future and her probable longevity. I repeatedly explained that this was a bad prognostic finding, and that her particular tumor was generally quite resistant to chemotherapy. She stated openly that she had no interest in taking chemotherapy or other treatments that would adversely impact the quality of her life. She then looked at me with tears in her eyes and asked, “Does this mean I won’t see you again?” I immediately replied that I would continue to see her on a regular basis throughout her life and that in my opinion part of the job for all of us in oncology is to support and care for our patients through all phases of the disease, even when our treatments have failed to eradicate the malignancy. I also confirmed that I respected her decision to decline chemotherapy treatment, and that I would assist her at any time. The patient smiled wanly, and reported that she was relieved that my colleagues and I would be available to treat any symptoms and help her should she develop any discomfort or other problems.

I continued to see my patient and the Professor every three months for another year. I arranged for consultation visits with physicians from our Palliative Care Service. Approximately fourteen months after I delivered the bad news that her cancer had recurred, the Professor called me and said that she was fading rapidly and they would likely not return. A month later I received a poignant and personal letter. In it, the professor included the obituary from the local newspaper regarding his wife’s death. It chronicled an impressive array of accomplishments and interests enjoyed over the course of a life lived fully. There was also a small hand painted watercolor card from the patient with a note to me. In it, she thanked me for giving her hope at that initial visit when I told her that it may be possible to remove her liver tumor with an operation. She then wrote something that I will never forget, “When I saw the other doctors, I felt rejected, trashed, and discarded. I felt they were dismissing me because they could not remove my cancer. All my hope was killed.” The note went on to thank me for giving her several additional years of life to enjoy traveling with her husband and spending time with friends and activities that were important to her. I make no apology to Friedrich Nietzsche or his acolytes, for I know that the death of hope is a much greater torment for patients than the presence of hope.

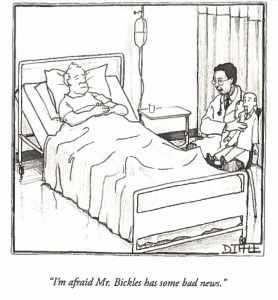

They didn’t teach a course on delivering bad news when I was in medical school, surgical residency, or during my surgical oncology fellowship. I often think of this cartoon by New Yorker cartoonist Matthew Diffee:

Delivering and receiving bad news is difficult for everyone involved in cancer care (and any other area of Medicine or life, for that matter): the patient, their family members, their friends, the physicians, and the members of the medical and nursing teams. We can’t have Mr. Bickles deliver the bad news for us and then walk away unscathed. There is an emotional toll taken on all of us. We can deliver bad news with compassion and care, and that should be the goal. Patients have the right to know that they are facing a battle with cancer that they will ultimately lose, but that physicians and other medical professionals will fight alongside them and support them and their family members. Supporting the family members of a cancer patient is too often a forgotten or unspoken component in cancer care, but one which requires mindfulness because all members of the family suffer and need support as they watch the disease progress and change their mother, father, son, daughter…whomever. One thing I learned early in my career is that patients may feel they will be abandoned by the medical profession when we can no longer treat or alter the progression of their cancer. Recall the words written by my patient, “I felt rejected, trashed, and discarded. I felt they were dismissing me because they could not remove my cancer.” Regardless of the outcome, I believe we must fight the battle hand in hand with our patients to the end, providing hope tempered with realistic expectations, discussion of possible symptoms and problems, compassion, and reassurance that we are there to help throughout the process.