We now know of almost 5,000 planets outside the Solar System. If you were to picture what it would be like on one of these distant worlds, or exoplanets, your mental image would probably include a parent star—or more than one, especially if you’re a Star Wars fan.

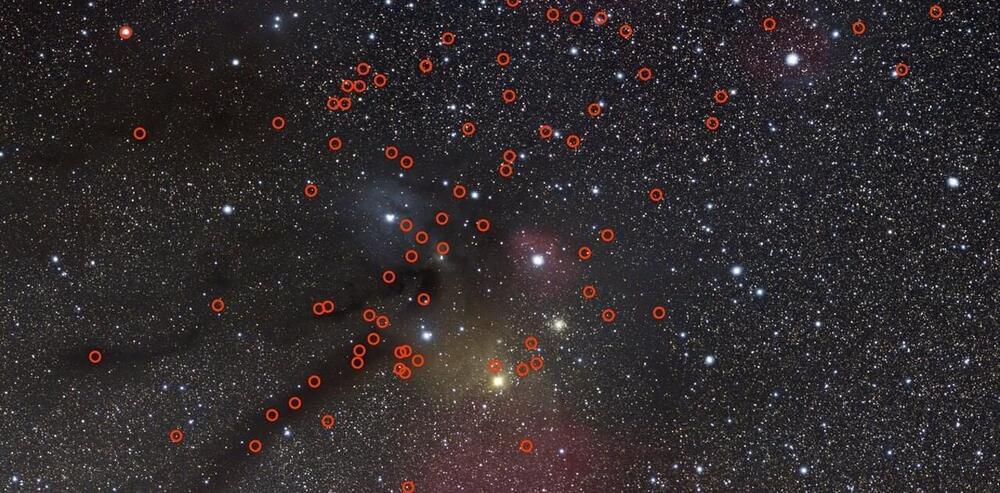

But scientists have recently discovered that more planets than we thought are floating through space all by themselves—unlit by a friendly stellar companion. These are icy “free-floating planets,” or FFPs. But how did they end up all on their own and what can they tell us about how such planets form?

Finding more and more exoplanets to study has, as we might have expected, widened our understanding of what a planet is. In particular, the line between planets and “brown dwarfs”— cool stars that can’t fuse hydrogen like other stars —has become increasingly blurred. What dictates whether an object is a planet or a brown dwarf has long been the subject of debate—is it a question of mass? Do objects cease to be planets if they are undergoing nuclear fusion? Or is the way in which the object was formed most important?