Researchers at EPFL have developed an approach to print tiny tissues that look and function almost like their full-sized counterpart. Measuring just a few centimeters across, the mini-tissues could allow scientists to study biological processes—and even test new treatment approaches—in ways that were previously not possible.

For years, mini versions of organs such as the brain, kidney and lung—known as “organoids”—have been grown from stem cells. Organoids promise to cut down on the need for animal testing and offer better models to study how human organs form and how that process goes awry in disease. However, conventional approaches to grow organoids result in stem cells assembling into micro-to millimeter-sized, hollow spheres. “That is non-physiological, because many organs, such as the intestine or the airway, are tube-shaped and much larger,” says Matthias Lütolf, a professor at EPFL’s Institute of Bioengineering, who led the study published today in Nature Materials.

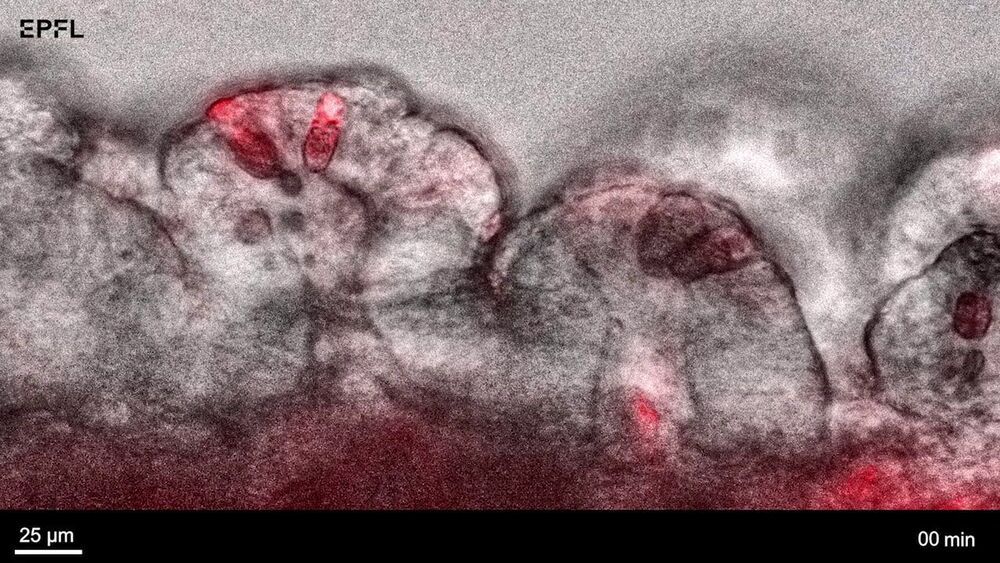

To develop larger organoids that resemble their normal counterparts, Lütolf and his team turned to bioprinting. Just as 3D-printers allow people to create everyday objects, similar technology can help bioengineers to assemble living tissues. But instead of the plastics or powders used in conventional 3D-printers, bioprinters use bioinks—liquids or gels that encapsulate living cells. “Bioprinting is very compelling because it allows you to deposit cells anywhere in 3D space, so you could think of arranging cells into an organ-like configuration such as a tube,” Lütolf says.